The 3 stages of a cop’s career

have similarities to a classic universal journey

By Ed Wojcicki

Published December 2019

Uploaded January 7, 2020

Command magazine

Illinois Association of Chiefs of Police

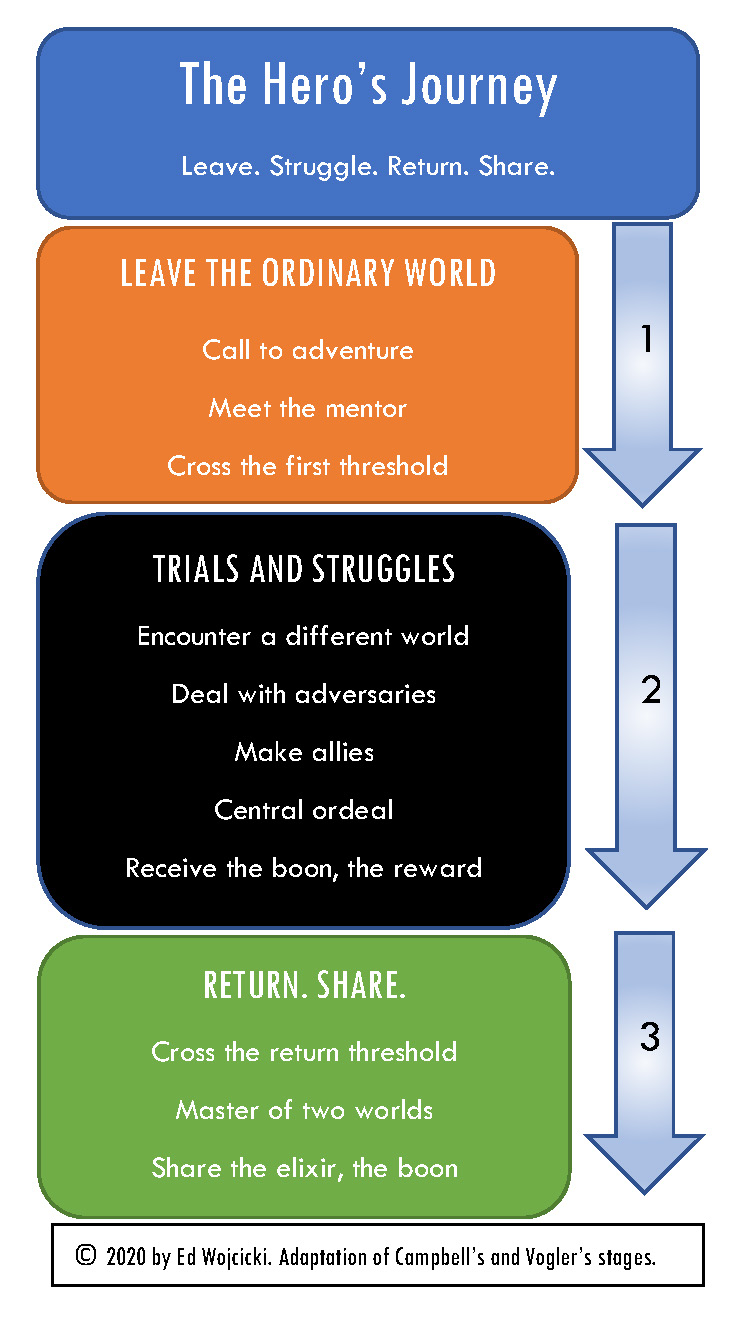

I HAVE BEEN READING about a journey that, as it turns out, most cops take. It can be simplified in three stages. This is how it plays out in a cop’s career:

- A person hears a call to adventure, leaves the ordinary world, and enters the academy

- As a sworn officer, he or she devotes one’s years to a world unknown to the rest of society – a world of chaos, struggles, and ordeals.

- The officer emerges from the unknown world and returns to the ordinary world a different person, personally and professionally. The growth happens gradually. Officers have mastered the underworld. They can share what they have learned by training others and becoming mentors. That makes them the master of two worlds.

In those three stages, I have just summarized what is known as the classic “Hero’s Journey.” This is a universal journey that is found in ancient mythology, some great books of fiction, and recent movies. And in the daily lives and careers of cops.

As soon as I say “hero,” some cops will mutter that I’m totally wrong. They might prefer Kevin Gilmartin’s succinct description that what cops do all day is deal with bullshit and assholes. Cops are reluctant to consider themselves heroes, except for those noble ones who die in the line of duty. But rather than call bullshit on the word “hero,” cops might benefit from seeing themselves and their comrades on this “hero’s journey” of personal sacrifice that becomes a benefit to society. As soon as I say “hero,” some cops will mutter that I’m totally wrong. They might prefer Kevin Gilmartin’s succinct description that what cops do all day is deal with bullshit and assholes. Cops are reluctant to consider themselves heroes, except for those noble ones who die in the line of duty. But rather than call bullshit on the word “hero,” cops might benefit from seeing themselves and their comrades on this “hero’s journey” of personal sacrifice that becomes a benefit to society.

The personal benefit is that cops can learn not only that all of the stages are normal and universal, but also that they have choices to make at every stage. The fundamental choice is to keep going, knowing there is more to learn, or to fade away in cynicism and bitterness (Gilmartin’s bullshit). At the fictional level, this is played out in in an intense scene in the second Star Wars movie when Darth Vader implores Luke Skywalker to join him on the dark side. Luke, of course, chooses not to do that.

THE CLASSIC HERO’S JOURNEY always has three stages: departure, a time of trials and struggles, and the return. Joseph Campbell, who studied mythologies in every culture, first articulated this journey in 1949. Almost thirty years later, film producer George Lucas read Campbell’s work and declared he could not have finished Star Wars without utilizing the hero’s journey. Lucas and Campbell became friends. Now it’s easy to see the three stages of the hero’s journey in Star Wars.

- Leave. Luke Skywalker leaves the farm after hearing the call to adventure.

- Struggle in an unknown world. Luke overcomes ordeals in the sewage and against Darth Vader and the Death Star.

- Return. Princess Leia honors Luke and Han Solo at the big ceremony.

After the Star Wars success, others in Hollywood “discovered” the hero’s journey. Consider Dances With Wolves, Raiders of the Lost Ark, The Lion King, and many more. It’s a new way of describing Act 1, Act 2, and Act 3, which is not a new structure. In The Wizard of Oz (1939), Dorothy leaves Kansas, endures many struggles on the yellow brick road, eventually triumphs, and is able to declare, “There’s no place like home.” Departure. Struggles. Return.

Okay, now an admission: The hero’s journey is more complicated than three stages. In his book, The Hero With a Thousand Faces (1949), Campbell identified seventeen stages in the hero’s journey. Screenwriter Christopher Vogler converted those seventeen stages to twelve, and these twelve stages are the basis of most current explanations of the hero’s journey. Other stages involve crossing thresholds, temptations, a refusal of the call to adventure, the emergence of mentors, being rescued, freedom to really live, the road back, and more -- too much detail for this column.

Lessons from the hero’s journey

There is a bigger point to all of this. There are indispensable lessons to be learned at each stage of the hero’s journey, whether you look at three, twelve, or seventeen stages. Here is a sampling of those lessons learned , explained in my own words:

- Mentors will be there when you need them. Think of Yoda and Obi-Wan Kenobi in Star Wars, Hagrid in Harry Potter, and Morpheus in The Matrix.

- You go through thresholds, and these transitions are perilous. You ultimately choose to go from one major stage to the next, and somebody is usually there to try and stop you. Think of Indiana Jones’ adventure to the ark’s location, and the pit of snakes.

- Stage 2, the time of struggles, is likely to be the longest and the most difficult in your life and in your career. Be prepared for this, for how long it is. Accept it. Life is hard. You might feel as if you’re in the belly of the beast a lot longer than you want to be. Knowing that this is normal and that others feel the same way helps you understand that all is not hopeless even when it appears to be.

- You will always have adversaries and naysayers. Always.

- Your rewards may be mostly internal, a deep sense of well-deserved satisfaction. The world will never know about all of your struggles and adversaries. The journey well-taken and the life well-lived is ultimately not about you.

- You return with an elixir and humbly share it with society. It often is the knowledge or experience you have gained, but it might be a physical item like the Ark of the Covenant.

- Your journey is part of a much larger universe. You do your part and celebrate the ordinary world. As a master of two worlds, you can become a servant leader and mentor to others.

By helping everyone else, therein lies your satisfaction and the meaning of your life. Which is why The Mighty Ducks and Hoosiers don’t qualify as hero’s journeys. In those stories, the protagonists’ suffering propels them to championships, their own glory. Nothing wrong with that. But heroes like cops go to work every day willing to sacrifice themselves for people they don’t know, have never met, and sometimes don’t like. Cops on the street are loathe to consider themselves heroes. They say instead, “We are just doing our jobs.”

They do so much more. They Leave. Struggle. Return. Share. Day after day, year after year. Usually, the return to the ordinary world is only the final five minutes of a movie. Did you ever notice that? I have timed it. In real life, “happily ever after” lasts a lot longer than five minutes. It lasts an entire career – years of self-sacrifice. For cops, that makes them always the servants, always the protectors, always the guardians. And always the heroes. They do so much more. They Leave. Struggle. Return. Share. Day after day, year after year. Usually, the return to the ordinary world is only the final five minutes of a movie. Did you ever notice that? I have timed it. In real life, “happily ever after” lasts a lot longer than five minutes. It lasts an entire career – years of self-sacrifice. For cops, that makes them always the servants, always the protectors, always the guardians. And always the heroes.

Ed Wojcicki is executive director of the Illinois Association of Chiefs of Police in Springfield. He can be reached at [email protected]. The last picture is that of a statue created by Brodin Studios for Freeport, NY. Brodin Studios has several versions of police statues called Protector.

|