|

Introducing the Eight Levels of Supervisory EngagementIdentifying (and then avoiding) disruptions, damage, and sabotage

By Thomas J. Lemmer

All who have worked any significant length of time in law enforcement have had an exposure to a wide variety of supervisors. Fortunately, many are inspiring leaders who can be relied upon for their proactive engagement, skill, knowledge, and leadership. They simultaneously safeguard their officers, successfully implement department strategies, and in so doing, they help their agency overall to meet its public safety mission – consistent with community expectations.

I have worked in public safety positions for forty 40 years, of which more than 34 years were with the Chicago Police Department (CPD), including nearly a quarter of a century as a supervisor. I remain inspired by that day’s vivid example of what “supervisory excellence” does not look like. Chicago is one of the nation’s most challenging policing environments, and CPD has developed some of the profession’s most impressive law enforcement leaders. However, the department has also had its fair share of lackluster supervisors and worse. For more than two decades, I directed, managed, and assessed CPD supervisors and command personnel. First, as a lieutenant, captain, and commander, and then ultimately as the deputy chief tasked with overseeing the department’s management accountability processes under CompStat. These roles provided many lessons about supervision.

A Model to Identify Supervisory Types:

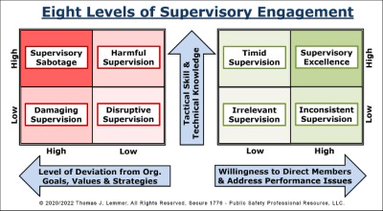

I created the “Eight Levels of Supervisory Engagement Model” to formalized what I had learned about the wide range of supervision within the profession. A fundamental truth of organizations, including law enforcement agencies, is that underperforming and problem employees exist. When the underperforming or problem employee is a supervisor, the need for the organization to respond is elevated. This is true even when supervisors are merely ineffective, as ineffective supervisors foster a less effective workforce. However, the impact on the agency is even worse, when supervisors do not support the organization’s values, goals, and strategies. With these supervisors, the need for the agency to respond becomes essential, as such supervisors can crush the organization’s ability to meet its mission.

All of us have seen a standard two-factor matrix. With the standard matrix, four “high-low” combinations quadrants are possible. Early on in the role of assessing the quality and effectiveness of supervision, two key factors were observable that helped to clarify the distinctions between police supervisors. However, in my experience, these two factors alone could not account for the full range of variations among the supervisors that I had encountered. As described below, a third factor was identified, which created two groups of four “high and/or low” combinations. In combining the two groups, there are a total of eight corresponding supervision levels. With the three variables, the model better addressed the full spectrum of observed supervision types.

The first factor, on the vertical axis, considers the level of technical knowledge and tactical skill. Both how well the supervisors know their job (and that of their subordinates), as well as their skills proficiency in turning their knowledge into action. While some supervisors may demonstrate a very limited level of knowledge and little skill in applying what they know, zero is still the bottom. As such, the model does not have or need a downward vertical, or “negative” variation, of this variable.

The second factor, extending to the right on the horizontal axis, examines the willingness of a supervisor to direct subordinates and proactively address performance issues. The willingness to take the initiative – to act, to ensure compliance with key policies, to address issues before they escalate – is an essential element of excellence. However, relative to this “willingness” to engage subordinates, a negative variation had been observed.

With some supervisors, the key question was less about their willingness to engage their subordinates, and more a question about the nature of their engagement. In short, some supervisors were rowing in a different direction. For these supervisors, the third factor, extending to the left along the horizontal axis, was best described as the level to which the supervisor has come to reject (that is deviate) from the organization’s values, goals, and strategies.

The Eight Engagement Levels:

Beginning with the left side of the matrix, we have the first four engagement levels. The greatest dangers to an organization occur when its own supervisors are not supportive of the agency or its mission. It is this internal opposition that comprises the negative variable of “Level of Deviation from Organizational Goals, Values and Strategies.” The negative impact of this group is heightened when the involved supervisor also ranks high for the “Tactical Skill and Technical Knowledge” variable. The A higher level of skill and knowledge can increase the credibility of these problem supervisors among many within the agency.

Moving to the right side of the matrix, we have the second group of engagement levels. Without question, organizations thrive when their supervisors exhibit high levels of two key variables. First, the level of a supervisor’s “Tactical Skill and Technical Knowledge” is again core to supervisory impact. Fortunately, with this group the impact potential of these supervisors is positive. As such, the horizontal assessment variable seeks to examine their “Willingness to Direct Members and Address Performance Issues.” In short, examining whether these supervisors are proactive in carrying out their duties.

Now What? Training on the Model:

The model also provides guidance on what can be done to foster supervisory excellence, as I remain under the impression that what we do as police officers matters. What we do as police supervisors and executives matters as well. Over the course of my career, I have interacted with supervisors from across all eight levels. Without question, unit and agency performance were directly impacted by the quality of their supervision. In working with supervisors to guide them toward excellence, 19 approaches proved useful.

The identified response strategies are: communication, coaching, training, direction, redirection, counseling, expectations setting, close monitoring, corrective action, delegation, mentoring, acknowledgement (praise), encouragement, goal setting, assignment matching, listening, collaboration, behavior modeling, and exit planning.

By identifying where a supervisor falls within the matrix, police executives can properly select from the 19 corresponding strategies to mitigate and eliminate negative engagement, while also providing approaches that foster supervisory excellence within the organization.

The model has been accepted by the Executive Institute of the Illinois Law Enforcement Training and Standards Board, and presented to police chiefs and sheriffs from across Illinois. Efforts to expand the reach of the model are ongoing, including directly with agencies committed to excellence. I remain committed to the pursuit of supervisory excellence within the profession, and assist wherever I can.

The Way Forward:

At this year’s annual conference held by the Illinois Association of Chiefs of Police (ILACP), I had the privilege to once again to present this model. What I had not anticipated was the timing of my session – immediately following the session on the “Ten Shared Principles.” The work of the ILACP in partnership with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) has been exceptional.

The identified principles acknowledge the sanctity of life, foster improved police-community relations, and emphasize the highest ideals of the policing profession. I have proudly added my firm’s name to the list of signers to the shared principles, and I encourage others to do so.

As police agencies continue to move forward, building and maintaining supervisory excellence will be key to both their successful implementation of these principles and their overall ability to enhance public safety.

Thomas J. Lemmer is the founder and president of Secure 1776 – Public Safety Professional Resource, LLC and a former deputy chief of the Chicago Police Department. He has extensive experience directing, managing and assessing law enforcement supervisors and executives. He holds B.A. and M.A. degrees in Criminal Justice, and for seven years he was an adjunct faculty member at Loyola University Chicago. He is a member of the International Association of Chiefs of Police, Illinois Association of Chiefs of Police, Illinois Sheriffs’ Association, Police Executive Research Forum, Police Futurists International, the Fellowship of Christian Peace Officers, and the Fraternal Order of Police, among other professional organizations. He can be contacted at [email protected].

|